Oregon lawmakers take the time to listen – by David Sarasohn

Oregon lawmakers take the time to listen – by David Sarasohn

April 20, 2017 – “I was a starving child,” said Darleen Deasee, and the words hung in the air of the Oregon House Majority conference room, which got very quiet.

“The only meal I got was lunch in school. At 10, I started stealing food. A grocery owner told me if I needed a can of soup I should just ask him. I would fall asleep in class because I was so hungry.”

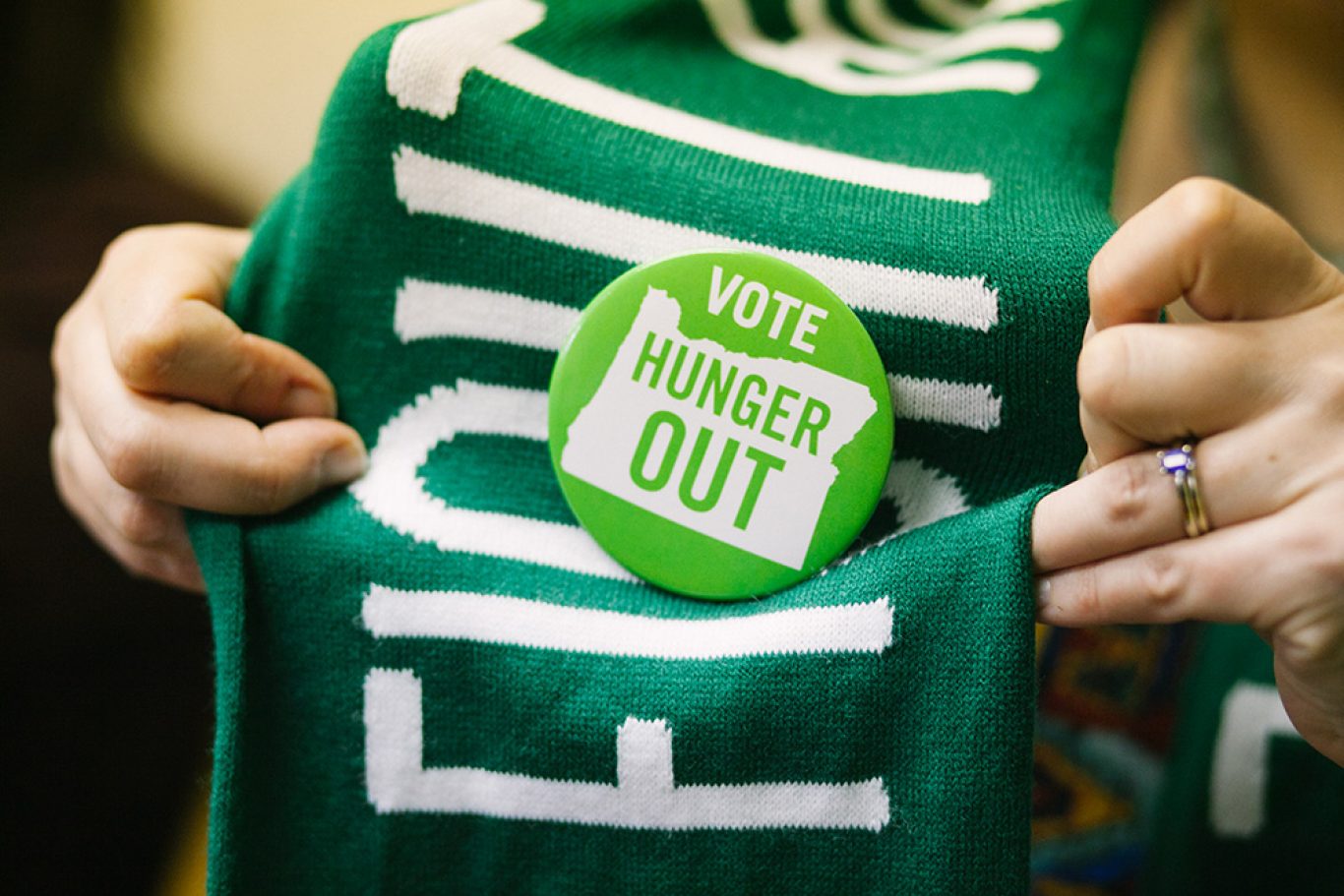

About half an hour before, in the state Capitol’s largest hearing room in the building’s basement, Jeff Kleen of Oregon Food Bank was talking to a crowd of Oregonians who showed up to lobby the Legislature about hunger. Wearing green scarfs reading “WE CAN SOLVE HUNGER,” looking like somewhat older and less manic Portland Timbers soccer fans, they listened to Kleen offer advice on how to persuade legislators to add another $800,000 to the Oregon Hunger Response Fund.

Be positive, he told them. Talk about community benefits. Keep the message simple.

Tell stories. Stories can change minds.

“College students are like anyone else,” Elizabeth Champion, the manager of the Portland State University food pantry, told her next meeting with a legislator. “It’s not whether they’re eating ramen, it’s whether they’re eating at all.”

“We started in a closet, and now we serve 4 percent of the students of Portland State.”

Starting at 7:45 a.m., the 250 citizen lobbyists mobilized by the food bank had appointments at the offices of all 90 members of the legislature. Legislators from more distant parts of the states might have a handful of visitors, a gathering fitting in their guest room-sized personal legislative offices. Members from closer districts might draw enough of a crowd, mostly constituents, to fill a caucus room, with tight legislative schedules meaning just a few of the visitors got to tell their story.

“Just about every Catholic church has a St. Vincent de Paul branch,” helping with food and other needs, related Matt Cato of the Archdiocese of Portland. “It helps to be a longtime Chicago Cubs fan. You’ve got to have hope.”

Legislators have different ways of listening. There’s their visibly open but clearly wary demeanor for questions from reporters. There’s the close, furrowed-forehead attention for professional lobbyists who want to talk about a bill’s paragraph (c) of Title VII.

Then there’s the taking-it-all-in, storing-it-away focus extended to constituents who are actually talking about their lives.

“I lost everything and ended up in a shelter” after a second bout with cancer, recalled Aletha, her voice shaking. “If it weren’t for the food bank, I’d be on the streets. These people are my family.”

Around the table, all the visitors who wouldn’t get to say anything this time listened intently, giving support, bearing witness.

“One of my schools had a food drive,” recounted Dan Crunican of Oregon Food Bank, who explained that he’d decided in his fifties that he’d made enough money and it was time to do something else. “A teacher told me she saw a student take food from the barrel.

“I said, it’s direct delivery. Let it go. Close your eyes.”

It turns out that when you offer legislators your stories, they have some of their own.

“I grew up in a pretty abject level of poverty, before food stamps,” remembered Sen. Richard Devlin, D-Tualatin, co-chairman of Ways and Means and the Capitol’s acknowledged authority on the state budget. “I ate a lot of cheese.

“It’s a very difficult year. But one thing that I look at is, there are things where you can make an investment and get a direct return to my people.”

And there is more than one way to get a return.

Every year the House and Senate have a food drive competition, and every year the House, with twice as many members would win, recounted Sen. Bill Hansell, R-Athena, a long way from his vast district in Northeast Oregon. The famously irritable Senate President Peter Courtney was irritated by the situation.

“Somebody said, ‘Why don’t you get some potatoes?’ and I thought, ‘Why not?’” continued Hansell, visibly enjoying the story as he told it. “So I called some farmers. We got a truck full of potatoes up here, 70,000 pounds.

“We smoked the House.”

For citizen lobbyists, that story even has a moral: Smoking the House can be done.